My problem with 3D printed houses

On complicating known processes without adding value

As someone involved in the tech and innovation side of the AEC industry, I see many articles, interviews, and conversations about technologies that will supposedly “revolutionize” the construction industry. The one that seems to be particularly popular as of right now is 3D printing houses, as done by companies such as ICON and Apis Cor. They promise to build stronger houses faster, safer, (and most important to the sales pitch of the technology) cheaper than traditional methods. I don’t plan to spend this whole post illustrating where I think the construction science and logistics failures of 3D printing houses comes from, as there are plenty of other sources that do just that. I’m going to start by laying out a past example of a method that would “change the industry”, my issue with 3D printed houses as well as where I think they could actually shine, before concluding with methods that are similar in scope but I think are more likely to succeed.

Shipping container houses gained popularity in the early 2000s as a new ‘sustainable and cheap’ housing solution. The idea of repurposing shipping containers into houses appealed to both those who care about the environment and those seeking affordable housing options. Initially, these structures garnered significant media attention and were hailed as a potential revolution in urban housing and emergency shelter solutions. To this day I will occasionally hear whispers on the wind about how reusing shipping containers could make for ultra cheap housing.

The reason why they haven’t exploded in popularity might not be obvious. They are rectangular, already structural, roughly the dimensions of a small house and importantly, already made. However, a house is more than a box. Bringing a shipping container up to livable standards requires a lot of expensive modification to meet code. Between the windows, doors, insulation, plumbing, fixtures and finishes, many of the cost savings of using an existing shipping container are lost. Even if they are mildly cheaper they also come in one set size, so unless your needs fit into some multiple of 8’x8’x40’, you also decrease the possibilities of your design. This isn’t to say it is never appropriate, just that the initial excitement one might get at the prospect doesn’t usually keep after reality sets in.

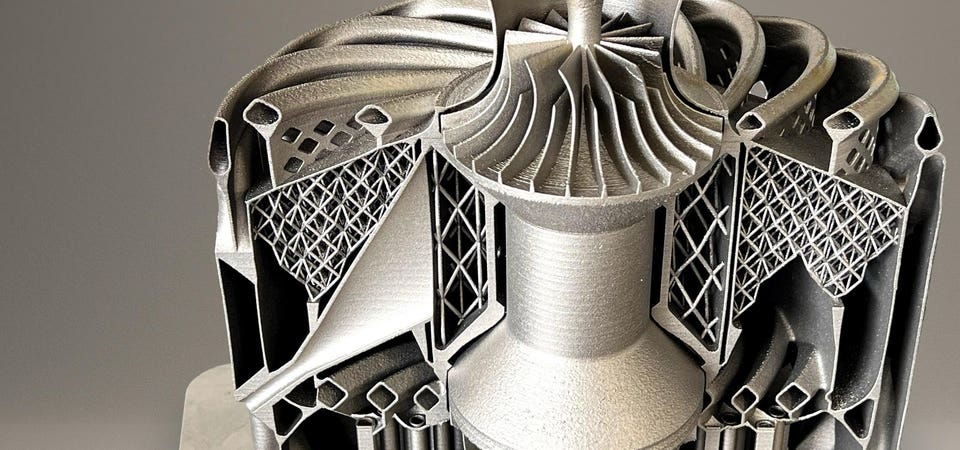

I’ve been into additive manufacturing for 4 years now. I continue to modify my printer as one might work on a project car, and I try to keep up with all the innovations in the field. Additive manufacturing is absolutely wonderful for making unique parts, for being able to prototype and iterate quickly, and for making certain geometries that are simply more difficult to make through traditional means. I’ve seen some wonderful examples of additive manufacturing to optimize rocket engines and ultra light weight structural parts. Putting custom parts into the hands of consumers for less than a TV and a little bit of desk space is fantastic.

My problem with 3D printing houses specifically lies more in the houses part than the 3D printing part. The construction industry has not been innovating, and it’s natural to look for technological solutions to help especially in our increasingly urbanizing world. Baumol’s cost disease is a principle that suggests that any field that doesn’t increase its productivity in line with the rest of the economy will get more expensive over time as labor becomes more expensive. Being able to put up houses faster, and with less required labor would most likely lend to construction ending up cheaper in the long run. So the 3D printer, the device which turns digital models into real objects, seems like the obvious candidate.

3D printers are very good at curves. They are also very good at creating more detail or complex geometries without adding much time. And as anyone who has used one knows, they have to be precisely calibrated and leveled or else they will have many print issues. So why are we proposing to build rectilinear houses with straight walls and unpredictable conditions with 3D printers? Between these issues and the fact that the plumbing, electrical, windows, insulation, and roof have to be done manually still, it seems like many of the currently proposed benefits get lost in the reality in the same way that shipping container houses did. But this does not mean they don’t have a place at all in construction.

As I said before, 3D printers are very good at curves and complex geometries. We should play into these strengths. Topology Optimization is the act of simulating the forces on a structure and removing the parts that add the least strength. The result is an organic looking structure that is lighter while maintaining most of it’s strength. These forms are usually very organic and would be a nightmare to make a cast of. Structures like this are exactly where 3D printing would shine. There has also been a lot of people rejecting clean modernism and want ‘Maximalism’. Highly ornamented structures, such as those in cathedrals, are becoming increasingly cheaper as manufacturing becomes more developed. Works like ‘Digital Grotto’ play into these strengths, and their cost as compared to traditionally manufactured objects of the same detail and scale is much lower. This PhD defense from MIT really highlights a lot of the strengths I couldn’t get to here.

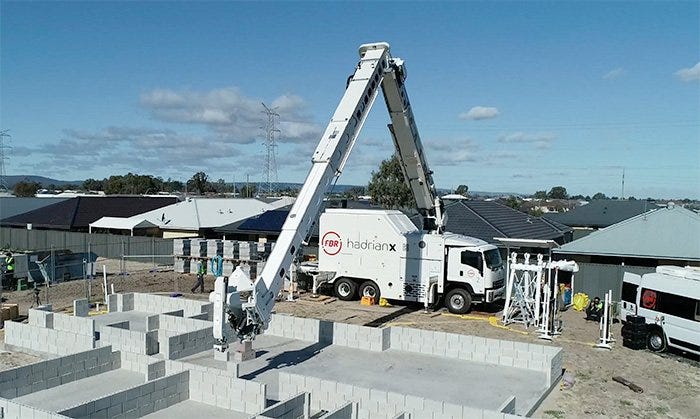

As for technologies that I think do have the capacity to make a dent in modern construction without majorly changing the types of houses we live in? Brick-Laying Robots, for one. You take all of the listed advantages of a 3D printer like high accuracy and less labor, but then put it on one of the most common construction types. Your house gets built faster, more accurately, but exactly as you’d expect a “normal house” to. Being able to use a single robot arm rather than a multi axis gantry allows it to simply be put on top of the same truck that brings in the bricks.

And my personal favorite innovation; off site construction. The idea of simply putting together most of your house in a factory before shipping it off to you seems much less glamorous than robot arms placing bricks or weaving concrete strips. But at the end of the day, we know how to make a good assembly line. Assembling parts off site can get you the same end product but with all the benefits of a controlled environment. There are less opportunities for major changes, but also less opportunities for major failures. This is not to say that off-site construction doesn’t have it’s own problems. In fact, there has been a string of modular construction companies that have recently filed for bankruptcy. This Belinda Carr video goes into it more, highlighting exactly why so many of them failed. Looking into the future, it is safe to assume that labor costs will rise and the prohibitive zoning codes that prevent prefabs will be lessened (fingers crossed). Hopefully these businesses will become more economically feasible, and won’t have to worry about ironing out so many technological kinks.