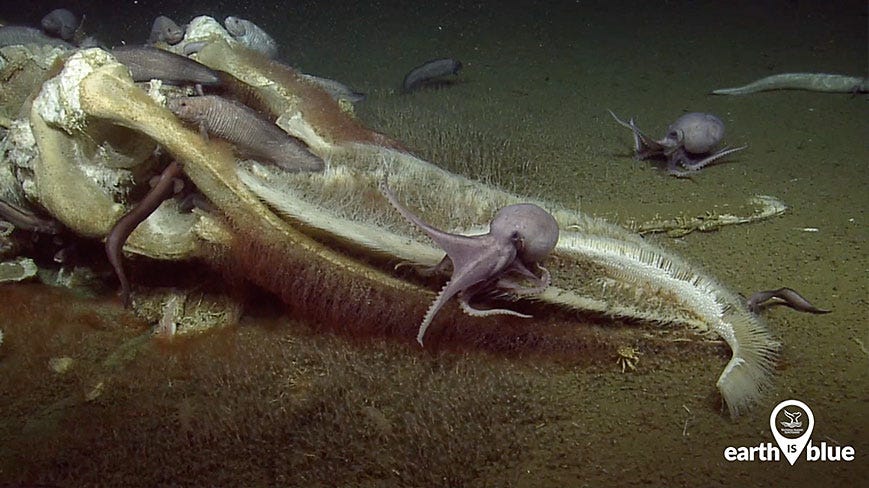

The death of a whale and its descent to the ocean floor creates one of nature's most revealing phenomena, the whalefall. This massive deposit of organic material transforms what appears to be an endpoint into the foundation of a complex ecosystem that sustains life for decades. Different organisms arrive to extract value from each stage of decomposition, from sharks and hagfish that consume soft tissue, to specialized Osedax worms that target skeletal remains, to bacteria that process the lipid rich skeleton. Nothing is wasted in this process, and this natural system offers a powerful way to understand urban development, particularly in spaces that traditional urban planning writes off as failures. Cities are undeniably the greatest engines of human prosperity ever created. The uncomfortable reality, though, is that much of this prosperity emerges from what we consider "failure spaces," informal settlements, declining industrial areas, zones of urban transition. These spaces, like a whalefall, create opportunities for different types of economic activity to emerge in layers. It would be absurd to expect a single species to efficiently process an entire whale carcass, and it is equally absurd to expect a single economic model to efficiently extract all potential value from urban resources.

Informal settlements don't simply exist alongside cities, they actively process urban waste streams in ways that formal systems never could. Mumbai's Dharavi, which is often mischaracterized as just a "slum," contains an intricate recycling ecosystem that processes thousands of tons of plastic waste annually. Workers sort through different types of plastics by hand, developing expertise that automated systems cannot match. Small workshops then transform this waste into pellets that feed back into the formal manufacturing sector. This isn't mere recycling, it represents economic transformation that creates value from what formal systems discard. The electronic repair and recycling communities in these settlements often develop technical expertise that surpasses formal businesses. In Ghana's Agbogbloshie, frequently mischaracterized as just an "electronic waste dump," repair technicians can diagnose and fix complex electronics with minimal tools. While there are serious problems with international theft and environmental hazards, focusing solely on these issues misses the incredible innovation happening there. In Rio's favelas, residents have developed sophisticated techniques for building on steep hillsides using reclaimed materials. These aren't makeshift solutions, they're innovations born of necessity that often outperform formal construction methods in similar conditions. The formal sector typically sees these as substandard solutions, but they're actually sophisticated adaptations to local conditions.

A counterintuitive truth emerges from studying these spaces, disadvantage often leads to better outcomes through forced innovation. In the early days of computing, programmers in countries with limited computing power often became significantly more skilled than their Western counterparts. When these programmers finally got access to better hardware, they frequently outperformed peers who had always had powerful computers, as they had learned to do more with less. This pattern repeats across different domains. Kenya essentially skipped traditional banking infrastructure, moving straight to M PESA and mobile money solutions, avoiding the inertia of an existing banking system. Bangladesh is doing something similar with solar power, using microgrids to leapfrog the entire era of centralized coal power plants. These aren't temporary solutions, they're potentially better approaches that emerged precisely because these places lacked established infrastructure. While cities with extensive subway systems struggle to adopt new transportation technologies, places with less developed transport infrastructure often adopt innovative solutions more quickly. Jakarta's informal motorcycle taxi system evolved into Go Jek, a super app that now handles everything from transportation to food delivery to digital payments.

Money moves differently through informal spaces, creating unique economic patterns that challenge conventional understanding. A salary that might seem modest by formal city standards can have dramatically larger impacts when circulated within informal settlements. In Brazil's favelas, small businesses often achieve higher returns on investment than similar businesses in formal areas, precisely because money circulates more times within the local economy before leaving. Lower overhead costs allow for more efficient resource use, alternative value chains create additional opportunities, local markets adapt more quickly to community needs, informal credit systems often work more efficiently than formal banking, and social capital often substitutes for financial capital. A small restaurant in an informal settlement demonstrates this pattern clearly, buying ingredients from local vendors, hiring local staff, using local repair services, and catering to local tastes, while the same business in a formal area might rely more on external supply chains, formal financing, and standardized processes, creating less local economic activity per dollar of revenue.

The governance structures in informal settlements reveal complex relationships between formal and informal institutions that shape urban development. Rigid informal governance systems can become incompatible with formal state institutions, creating competing systems of social order that extend beyond simple issues of crime or regulation. In Rio's favelas, residents often prefer to take disputes to local community leaders rather than formal courts, even when they have access to both, as informal systems often work more efficiently for daily needs but can become barriers to larger scale development. While formal systems rely on written documentation and centralized records for property rights, informal settlements often have sophisticated social systems for recognizing ownership and resolving disputes. These systems might look chaotic from outside but often work more efficiently than formal alternatives for local needs. Traditional urban planning often tries to impose formal systems from above, but this typically fails because it doesn't recognize the efficiency of existing informal arrangements. The challenge lies not in replacing these systems but in finding ways to bridge them with formal institutions.

The global distribution of layered economic activity raises questions about urban development patterns. Currently, much of this layered activity happens globally as we outsource jobs to places with lower capital and labor costs, but maintaining these different economic layers more locally within urban areas could provide significant benefits. Instead of shipping waste across continents for processing, more robust local ecosystems for material reuse could reduce transportation costs and environmental impact while creating more resilient local economies, better integration of formal and informal sectors, stronger community connections, more efficient resource usage patterns, and faster adaptation to local needs. Asian cities demonstrate this potential in their food markets, where formal supermarkets, semi formal street markets, and informal vendors all operate in the same area, each serving different needs and price points, creating a layered approach that works better than forcing everyone into a single formal system.

Constraint driven innovation appears repeatedly in these environments, producing solutions that formal systems struggle to replicate. In India, "jugaad" innovation creates maximum value from minimal resources through creative repurposing of materials, development of alternative supply chains, novel approaches to service delivery, innovative financing mechanisms, adaptive reuse of space, and resource efficient technical solutions. Informal settlements often develop sophisticated systems for water sharing, storage, and reuse that are more resilient than formal systems, demonstrating innovations that formal urban planning could learn from. The whalefall metaphor suggests several principles for urban development, valuing organic bottom up development, maintaining multiple economic and social layers, allowing for natural succession and transformation, recognizing the importance of temporary and transitional spaces, and supporting rather than replacing existing systems. Traditional zoning often tries to separate different types of economic activity, working against the natural layering that makes informal economies so efficient, while some cities experiment with more flexible zoning that allows for mixed use and gradual formalization.

Urban development requires a fundamental shift in perspective, mirroring how marine biologists have learned to value the role of whalefalls in ocean ecosystems while still working to prevent whale deaths. This isn't about romanticizing poverty or accepting dangerous conditions, but recognizing that what looks like failure from one perspective might be innovation from another. The messy, organic development of informal settlements might have more to teach us about sustainable urban development than our formal planning models. Urban spaces that seem like failures by traditional standards often contain hidden layers of activity and emerging innovations born from constraints and challenges. What looks like decay from one perspective might actually be the foundation for something new and valuable, if we have the wisdom to recognize it and the patience to let it emerge. In nature's economy, nothing is truly waste, it's just resources waiting for the right organism to make use of them, and perhaps our cities could work the same way, if we let them.